New information on Social Security Disability by: Damian Paletta

Government Pulls in Reins On Disability Judges

WASHINGTON—The Social Security Administration, smarting from recent scandals, this weekend is set to tighten its grip on 1,500 administrative law judges to ensure that disability benefits are awarded consistently and to rein in fraud in the program.

WASHINGTON—The Social Security Administration, smarting from recent scandals, this weekend is set to tighten its grip on 1,500 administrative law judges to ensure that disability benefits are awarded consistently and to rein in fraud in the program.

The agency is rewriting the job descriptions of its judicial corps, allowing officials more latitude to crack down on judges who are awarding disability benefits outside the norm.

Many judges have operated as if they were independent of the agency and awarded or denied benefits based on their own judgments. A few weeks ago, the SSA notified the judges of the changes.

The job descriptions will no longer include the words “complete individual independence,” and will also clarify that the judges are “subject to the supervision and management” of other agency officials, according to a draft reviewed by The Wall Street Journal.

The changes are among a number of revisions the SSA has adopted in the wake of a several recent scandals, including the arrest of more than 70 people in Puerto Rico and a separate criminal investigation into a former judge in West Virginia. Both affairs raised questions in Congress about how much fraud might be in the disability adjudication system. Rep. James Lankford (R., Okla.) chairs an oversight subcommittee that monitors Social Security. Associated Press. The Social Security Disability Insurance program, funded by payroll taxes, pays monthly benefits—often until someone receives retirement benefits in their 60s—for people who can no longer work because of physical or mental health problems.

The changes are among a number of revisions the SSA has adopted in the wake of a several recent scandals, including the arrest of more than 70 people in Puerto Rico and a separate criminal investigation into a former judge in West Virginia. Both affairs raised questions in Congress about how much fraud might be in the disability adjudication system. Rep. James Lankford (R., Okla.) chairs an oversight subcommittee that monitors Social Security. Associated Press. The Social Security Disability Insurance program, funded by payroll taxes, pays monthly benefits—often until someone receives retirement benefits in their 60s—for people who can no longer work because of physical or mental health problems.

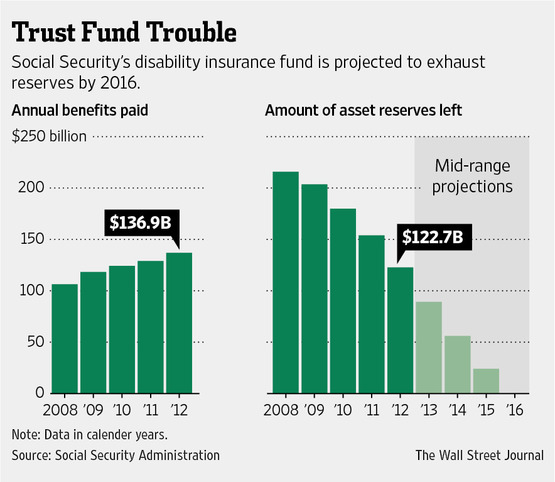

During the recent economic downturn, the program grew quickly and now has close to 11 million beneficiaries. It has grown so fast, in fact, that it is projected to exhaust the reserves in its trust fund by 2016, which could force all beneficiaries to see an immediate cut in their payments.

In 2011, The Wall Street Journal reported a wide disparity in the probability that certain judges would award benefits. Dozens of judges awarded benefits in more than 90% of their cases, while others were much less likely to find someone unable to work, denying benefits in more than 80% of their cases, data showed.

After the published report, the agency began tightening control over judges deemed “outliers,” but it also complained that “judicial independence” prevented SSA officials from intervening, even if a judge paid benefits in more than 95% of the cases.

Critics of the system say many changes are necessary to combat abuse, especially at a time when the disability trust fund is threatened.

“The economic recession and slow and weak recovery combined with the perceived ease with gaining benefits in federal disability programs has led many individuals who are not disabled to apply for benefits,” read a letter signed by Rep. James Lankford (R., Okla.) and two other lawmakers to SSA acting commissioner Carolyn Colvin this month. Rep. Lankford chairs an oversight subcommittee that monitors Social Security.

The union that represents many of the judges complains that the change will strip them of independence and open the process to political meddling. The judges are selected by the agency after a screening process, and their jobs tend to focus exclusively on hearing disability appeals and deciding whether or not to award benefits. In all, the judicial corps decide several hundred thousand cases each year.

Many judges also say they have faced constant pressure from senior officials to move cases in recent years, and many have responded by approving a large number of cases, according to interviews with several judges. The process was known within the agency as “paying down the backlog.”

The process of applying for benefits is complicated and multilayered. If someone is denied for benefits after an initial screening, they can appeal and request to have their case heard by an agency judge.

When the agency began tightening scrutiny over the judges two years ago, after the publication of the Journal articles, many judges changed their behavior.

In 2010, for example, judges awarded benefits in 67% of their 585,855 decisions, according to federal data. By 2013, the award rate fell to 56%.

“The allowance rate right now is probably at a 40-year historic low,” Social Security Administration Deputy Commissioner Glenn Sklar said at a congressional hearing in November.

However, the agency’s changes are expected to do little to thin the ranks of beneficiaries. In 2003, the agency paid $71 billion in disability benefits to 7.6 million people. By 2012, the agency was paying $137 billion in benefits to 10.9 million people.

SSA spokesman Mark Hinkle said the change came about because the existing job description had been in place for 17 years. Mr. Hinkle said the new description “appropriately preserves [the judges’] qualified decisional independence.”

But the judges have tried to block the move amid fears that they will be told how to decide cases by agency officials.

“They could take disciplinary action against a judge basically controlling the outcome” of any particular case, said Randall Frye, a Social Security judge who is also president of the Association of Administrative Law Judges. “That’s bad either way, and it could be bad under different [political] administrations.”

In the meantime, the judges’ behavior is having a noticeable effect, according to lawyers and others who represent people applying for benefits.

“It’s getting harder, especially with younger claimants or people who have been incarcerated,” said Geri Kahn, an immigration and disability lawyer with offices in northern California. “Cases that I think I could have won a couple of years ago, I’m not winning or I’m not taking.”

By DAMIAN PALETTA

Updated Dec. 26, 2013 8:14 p.m. ET